- Home

- Brian Kevin

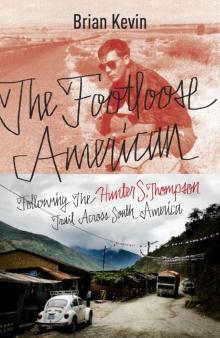

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America Page 3

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America Read online

Page 3

“Jesus Christ is coming back! Jesús Cristo va a regresar!”

I heard the bearded and wild-eyed street preacher before we’d even stepped out of the puerta-a-puerta. It was an uncharacteristically cool evening in the beachside village where we stopped for dinner, and a handful of locals were loitering around an open-air market, sipping refrescas and trying to ignore the ragtag prophet howling in the street. At our driver’s urging, we filed out with our fellow passengers, lining up at a street-corner grill for some cheese-stuffed corn pockets called arepas, the de facto national street food of Colombia.

“He is bringing you his blood!” yelled the preacher, addressing no one in particular. “Jesús Cristo le ofrece su sangre!”

Sky looked at me and rolled his eyes. The air was heavy with the buttery scent of frying arepas. In line in front of us, a stocky middle-aged guy who’d been riding shotgun in the van turned around and pointed none-too-subtly at the preacher.

“You see that guy?” he asked in Spanish. “That guy is an asshole.”

I blinked and begged his pardon.

“He’s an asshole!” said the guy again, a little louder this time. “He used to be a hit man for the cartels, and now he stands out here screaming about salvation.”

In the road, the street prophet was literally thumping his Bible with a fist, his knees bent and back arched like a soccer goalie in his stance. He looked like a cross between Cesar Romero and how I’d always pictured John the Baptist, his elastic face hidden behind a bird’s nest of a beard. He looked ready to tackle someone.

“These fucking guys,” our companion snorted dismissively. He shook his head. “All these evangelicals, these born-again guys? They’re the ones who used to do the really bad things.”

We paid for our arepas and piled back into the van, passing the preacher as he waved his arms and moaned. His pupils were grotesquely dilated, a pair of total eclipses, swallowing the light. As the van pulled away, the shotgun guy leaned out the window for a parting taunt.

“Hey, asshole!” he yelled. “Killed anybody lately?”

The preacher turned to face the van, nostrils flaring above a wild tangle of a mustache. For an instant, I pictured him opening his Bible, retrieving a pistol from the hollowed-out compartment inside, and firing on the van with an assassin’s deadly precision. Instead, our driver widened his eyes and hit the gas. As the van screeched away, the preacher shook his fists and yelled back that we were all sinners and all going to die. I decided to take this as an ontological prediction rather than a personal threat.

The instigator up front introduced himself as Alex, and the rest of the way to Riohacha, he told us about his own messy history with the cartels. As a teenager, he’d fallen in with local drug smugglers and helped move cocaine up and down the coast in a speedboat, which eventually led to a stint under house arrest in his twenties. He was surprisingly nonchalant about this, discussing it as if everyone in the van had been in the cocaine biz at one time or another. And for all I knew, this might have been true. When the three of us stepped out at Riohacha a couple of hours later, Alex offered us a ride and invited us to join his family for dinner.

We met up with his wife and twentysomething daughter at a beachside boardwalk, and the five of us ate cups of shrimp salad from a row of vendor stalls. Riohacha seemed charming, its boardwalk bustling with families and couples holding hands. The city sits at the base of the Guajira Peninsula, a Caribbean vacation town for middle-class Colombians and a hub for a booming industry in offshore natural gas. Alex and his family led us on a brief tour of the waterfront, all palm trees and wide parkways lined with Wayuu artisans and their woven baskets. The air smelled like salt water, and the seaside district seemed to be enjoying some prosperity. At one point, we passed a brand-new museum sponsored by Chevron, dedicated entirely to the wonders of natural gas. It was closed, but La Sala Interactiva Étnica del Gas looked like a lovely and modern facility, despite a name that translates awkwardly to “The Interactive Ethnic Gas Chamber.”

It was Alex who introduced us to Bernie, the truck-driving barkeep. Recently, Alex said, a few small ecotourism companies had popped up in Riohacha, leading travelers onto the peninsula on guided 4 × 4 tours. He wasn’t sure where to find any of them, though, and anyway, he knew a guy who could do it cheaper. So following our post-dinner stroll, we drove with Alex’s family to an unlit, residential part of town. Alex borrowed my cell on the way over (his was out of minutes) and chatted to someone in a diphthong-heavy language that I imagined to be Guajiro.

We pulled up in front of a small cinder-block home with a dirt bike out front. Bernie was waiting for us outside. He was a fit-looking Wayuu in his mid-forties, with the dark eyes and slight build characteristic of his people. When we hopped out of Alex’s truck, he smiled at us warmly and shook hands.

Bernie had spent most of his life on the peninsula, Alex said, by way of introduction. He owned a pool hall in a coastal village called Cabo de la Vela and occasionally moonlighted as a guide. Sure, Bernie said, he’d be happy to show us around Guajira. He’d been meaning to restock his beer cooler up there anyway. At that moment, his truck was with a mechanic in a town called Uribia, about a quarter-way up the peninsula, where the paved road ends. But if we could meet him there the next morning, we could head out from there, and Bernie said he’d even let us crash at his place in Cabo. Alex offered to arrange our ride to Uribia with a taxi-driver friend, and the next thing we knew, we were hashing out a fee, shaking hands once more, and piling back into the truck. Sky and I barely said a word during the entire negotiation.

By the time we finally checked into a hostel that night, our heads were spinning at how fast the whole thing had come together. We’d been prepared for much worse. In “A Footloose American in a Smugglers’ Den,” Thompson wrote with frustration about Guajira’s severe inaccessibility. Trying to get anywhere on the roadless peninsula, he said, “can turn a man’s hair white. You are simply stuck until one of the Indians has to run some contraband.” But with next to no effort on our part, Sky and I were all set up, ready to go full shit into the heart of contraband country.

Thompson paddled up to the tip of South America in a small rowboat, tossed by the waves and overburdened with luggage. He’d have cut a strange figure coming ashore: a bedraggled would-be foreign correspondent humping an unwieldy typewriter and a mess of camera gear. The Aruban smugglers had put him ashore at a village called Puerto Estrella, where he’d spend the next several days with confused Wayuu natives before making his way inland. He described the village in the Observer as having “no immigration officials and no customs.” He continued:

There is no law at all, in fact, which is precisely why Puerto Estrella is such an important port. It is far out at the northern tip of a dry and rocky peninsula called La Guajira, on which there are no roads and a great deal of overland truck traffic. The trucks carry contraband, hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of it, bound for the interiors of Colombia and Venezuela.

Guajira does indeed have a long tradition of both smuggling and general lawlessness. Throughout the colonial era, the obstinacy of the Wayuu people kept the Spanish colonizers more or less at bay. Missionaries infiltrated in the early twentieth century, but up until then, the peninsula was essentially a no-man’s-land, off-limits to non-indigenous Colombians. Even after the Department of La Guajira was formally created in 1964, the area stayed effectively autonomous, and to this day, it’s still something of a frontier. The vast majority of the peninsula is inside Colombia, but the Venezuela border slices across its southeast corner, bisecting the Wayuu’s traditional homelands. As a result, tribal members enjoy dual citizenship and can cross the border freely, avoiding established checkpoints. This arrangement, combined with hard-to-police coastlines and an overall lack of state authority, is why Guajira has historically been a “smugglers’ den.”

Cheap consumer goods are routinely carried over by the Wayuu from Venezuela, who pay only a token tariff and sell them on the pen

insula at a markup. Other Venezuelan products come across via clandestine overland truck routes, bypassing customs agents along the established roads. Cheap Venezuelan gasoline is routinely smuggled across the porous border. Still other goods arrive by cargo boat from free-trade zones like Panama and Aruba, to be unloaded in sparsely regulated backwater ports like Puerto Estrella. Of course, some of this trade is legit. In the 1990s, the Colombian government took an adaptive approach and abolished the tariffs on certain goods intended for local use. But even much of that merchandise eventually finds its way into mainland Colombia via desert routes or bribes to customs and police. In 2012, those agencies seized around $128 million worth of smuggled goods, but the government estimates that 90 percent of contraband in Colombia still goes undetected.

Whatever its origin, then, chances are good that any product you purchase in Guajira has found some way to evade import taxes. And on our way to meet Bernie, Sky and I asked our taxi driver to stop off at the Chicago Stockyards of this desert smuggling scene, a dusty metropolis called Maicao, about ten miles from the Venezuelan border.

The sprawling street market in Maicao is a sort of a contraband Costco, filled with shoes, clothing, cigarettes, liquor, dog food, bike parts, and kids’ toys—most any imaginable consumer item under the sun, all sold by Wayuu merchants at ridiculously cheap prices. While Sky wandered around shooting photos, I browsed the stalls and chatted up vendors. I noticed quickly that communication in Maicao was easier for me, since many of the locals spoke equally rudimentary Spanish, preferring instead their native Guajiro, a Caribbean Arawak language that Thompson described as being “a bit like Arabic, which doesn’t ring well in a white man’s ear.”

For the price of a latte, I bought a bottle of Scotch from a teenaged girl who giggled as she gave me my change. Despite the contraband status of the merchandise, the bazaar at Maicao had the same warmly chaotic atmosphere as your average Saturday-morning farmers’ market back home. It was bustling with people. A band in the center square played vallenato music, a favorite Colombian mixture of accordion, sappy lyrics, and African hand drums. On a side street, a row of fifty live goats lay bleating, their legs tied up, each one stacked atop the next like a row of fallen dominoes. Behind all this was the ubiquitous urban soundtrack of car horns and idling engines—although, as Sky pointed out, even the street traffic was unique.

“You see these cars?” he asked as we met up by the goats. “Land Cruisers? F-150s? That’s the kind of car you drive only if you have access to cheap gas. You would never see huge cars like this on the streets of Bogotá or Medellín.” And indeed, on our way out of town, our taxi driver pulled over to buy gas from a ten-year-old boy on the side of the road, a wide-eyed Guajiro-speaker who sold it by the gallon from fluorescent plastic jugs.

Thompson had also noted the trappings of affluence around the otherwise hardscrabble Puerto Estrella. To a description of the natives’ poverty and simple style of dress, he added this wry postscript: “A good many of the men also wore two- and three-hundred-dollar wristwatches, a phenomenon explained by the strategic location of Puerto Estrella and the peculiar nature of its economy.” Had F-150s been available in 1962, he probably would have spotted a few parked conspicuously around the village.

But after a decades-long and fairly benign run, smuggling in Guajira has become a source of controversy. When Colombia’s “law-and-order president,” Álvaro Uribe, came to power in 2002, his government started cracking down on the region’s black markets for essentially the first time in Colombian history. Lost tax revenue was one motivation, but Guajira’s smuggling biz has also developed a more sinister aspect in the years since Thompson’s visit. In recent decades, Colombia’s perennially active left-wing guerrillas and right-wing paramilitaries have exploited Guajira’s geography and lax regulation to smuggle drugs, run guns, and skim off the top of the Wayuu’s smuggling profits via extortion. While the country’s main paramilitary group, the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, or AUC, has been officially disbanded since 2006, mafioso-like former “paras” have increasingly taken over the most profitable smuggling rackets. In 2003, the Colombian government helped set up Wayuu petrol cooperatives, hoping to undercut smugglers by enabling the tribe to legally import Venezuelan gasoline. Over the next few years, though, one co-op board member was murdered while numerous others resigned under duress. The co-op’s tankers have been bombed and customs agents killed in encounters with both guerrillas and former paras. Today, Guajirans like Bernie will likely tell you that the latter group essentially controls gasoline imports, and accounts of smuggling-related violence seem to crop up in human-rights bulletins every few months.

All of this helps earn Guajira its Wild West reputation, but it also raises difficult questions about the Wayuu’s relationship to the rest of their country. Reports by indigenous advocates and international aid groups tend to paint Guajira as a victimized region, a place where the troubles of an often-violent country have “spilled over” to affect the unaligned natives. And certainly, the smuggling biz hasn’t much empowered the Wayuu. Guajira is one of Colombia’s poorest departments, where, according to the country’s National Planning Department, some 65 percent of its households find their basic needs unmet. Of the roughly 150,000 Wayuu living on the Colombian side (there’s a slightly higher number in Venezuela), maybe 10,000 or so draw paychecks from multinational energy companies—mining natural gas for Exxon or coal at a large open-pit mine south of Maicao, called Cerrejón. The rest are mostly pastoralists, getting by on some combination of goat-herding, sales from contraband, and seasonal migrations for temporary work in the cities.

On our way out of Maicao, we saw a testament to the Guajiran subsistence mentality. A few miles outside of town, our taxi passed a Wayuu driver whose dented Honda had just hit and killed three goats. By the time we pulled over to offer some help, the driver was already tossing one of the carcasses into the rear of his hatchback. “I’m taking them with me.” He shrugged without smiling. “It’s money, right?”

As I watched that driver shoulder his road-kill goats—or the somber, brown-skinned kid pouring gas into the taxi—it might have been easy to accept this notion of a Wayuu people who’ve been shoved somehow from an aboriginal state of grace. This seems to be our default, twenty-first-century narrative about indigenous people, after all, and not without good reason. But arriving for the first time in South America, the mid-twentieth-century Thompson didn’t see things this way. His account muddies the waters a bit, portraying the Wayuu as willing accomplices in Guajiran vice, complicit in the peninsula’s underworld going back at least half a century.

“It would not be fair,” he wrote obliquely, “to say that the Indians arbitrarily take a healthy cut of all the contraband that passes through their village, but neither would it be wise to arrive and start asking pointed questions.”

As Sky and I approached the end of the paved road in Uribia, I wondered which Guajira we would find on the other side—the lawless twenty-first-century outback or the primitive paradise lost.

It took a few tries to start Bernie’s ancient blue Toyota, but eventually we shuddered out of the mechanic’s yard in Uribia and down the road to a bodega, where Sky and I helped load twenty-one cases of impossibly cheap Venezuelan beer. Far from being flush with the profits of illicit smuggling, Uribia was kind of a dump. The town’s dusty streets were littered with ragged plastic bags, so many that it seemed impossible for the tiny desert outpost to have produced them all. On the way in, we passed a dry creek bed filled with bags. They fluttered like prayer flags on the cactus fences and got caught underneath the tanker trucks that supply Uribia with fresh water. Many of the bags had been sun-bleached to pale pastels that bordered on colorlessness. In fact, the most vivid colors in the seemingly all-beige town came from the bright patterned frocks of the Wayuu women, called mantas guajiras, which looked a little like burqas but more festive and without the veil. The men, on the other hand, dressed like cowboys in blue jeans and Stetsons.

It was a far cry from the borderline savages that Thompson described: Wayuu villagers wearing nothing but neckties as loincloths. “I decided that at the first sign of unpleasantness,” he wrote, “I would begin handing out neckties like Santa Claus—three fine paisleys to the most menacing of the bunch, then start ripping up shirts.”

Within an hour, Bernie, Sky, and I were going full shit through the Guajiran desert, racing along a thoroughly rutted jeep track with nothing on the skyline but a shimmering blue mirage that I initially mistook for the Caribbean. As Bernie’s Toyota hammered its way across the scrub, Sky and I gave up pretty quickly on trying to drink the beer, concentrating instead on staying grounded in the truck bed. The thunder of Bernie’s engine made it impossible to be heard, and my tailbone rattled with every hummock, but I felt for the first time like we were really traveling in Thompson’s footsteps, and I could see from his grin that Sky did too. In my head, I played back Thompson’s exhilarated description of driving across the peninsula, “roar[ing] through dry river beds and across long veldt-like plains on a dirt track which no conventional car could ever navigate.”

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America