- Home

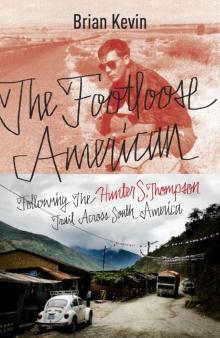

- Brian Kevin

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America Page 2

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America Read online

Page 2

Thompson’s plan happened to coalesce with the launch of the National Observer, an upstart newspaper founded in February 1962 by the Dow Jones Corporation. The Observer was an early experiment with the concept of a national newspaper, a sort of precursor to USA Today. It was a weekly paper aimed at an educated readership, with an emphasis on in-depth reporting and analysis that the quick-turnaround dailies couldn’t match. At around 200,000 readers, its initial circulation was smallish (Dow Jones’s flagship paper, the Wall Street Journal, reached nearly 800,000 at the time), but the novelty of a weekly national newspaper attracted a lot of attention in media circles, so the Observer was widely read and discussed among influential writers and editors at other publications.

The fledgling paper was actively seeking contributors, and when Thompson wrote about the prospect of submitting a few articles from South America, the Observer’s editors encouraged him to send whatever seemed like a good fit. It was all the invitation that Thompson needed.

“I am going to write massive tomes from South America,” he declared in a letter just three days after the Observer’s inaugural issue. “I can hardly wait to get my teeth in it.”

All of this I explained over e-mail to Sky, who wrote back that he’d had no idea Thompson was once a foreign correspondent. This, I said, wasn’t surprising. The year that Thompson spent down south is a period in his life that his biographers have all but ignored. In the years since the author’s death, dozens of “lost interviews,” biographies, and remembrances have offered glimpses of Thompson the man, but most tend to focus on his later career and the eccentric character he came to adopt. To some degree, this neglect of Thompson’s South American reportage is understandable. He is, after all, a writer whose name has become synonymous with the oddities and ugliness of US culture. Thompson famously proclaimed his beat to be “the death of the American dream,” and outside of those few early letters, his own writing rarely mentions his young adventures abroad.

But Thompson’s South American pilgrimage shaped, in no small part, the edgy journalist who came to national attention not long after his return to the States. Before setting out for South America, Thompson was a wannabe novelist and photographer, a post-Beat dilettante more concerned with short stories than social movements. He fervently identified with Lost Generation writers like Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, and Dos Passos, and he often looked down his nose at the grind of workaday journalism, dismissing it as a soul-sucking task to be undertaken only for a paycheck.

The Hunter Thompson that America came to know—the freewheeling correspondent, the caustic social chronicler—that Hunter Thompson was born in the streets of Rio de Janeiro, the mountains of Peru, and the black-market outposts of Guajira. It was in South America, in fact, that Thompson developed his razor-edged understanding of the dying American Dream.

“After a year of roaming around down here,” he wrote at the end of his journey, “the main thing I’ve learned is that I now understand the United States, and why it will never be what it could have been, or at least tried to be.”

That line had puzzled me since I first read it in The Proud Highway nearly a decade before. Just what did Thompson mean by this? It’s a declaration that stands in stark contrast to another that he made about five months before the trip. In January 1962, Thompson wrote to a friend in Europe, scoffing at the idea that travel might meaningfully alter one’s perspective on the United States.

“I doubt that a man has to go to Europe, or anywhere, for that matter, to understand the important things about this country,” he wrote. “Maybe he has to go to Europe to be prodded into articulating them, or before they seem worth talking about, but I think we have enough space and perspective over here so a man can step off into a corner and get a pretty good view.”

But Thompson found something in South America that dramatically reshaped his views on home—that dramatically reshaped him. The Thompson who left for the continent in 1962 was a self-identified seeker and escapist. The one who came back a year later was a narrow-eyed critic of American political culture and social ritual. If The Proud Highway became one of my favorite books as a college student, I think it’s because it offered a tantalizing glimpse at the nomad who came in between, and I wanted to better understand that transition. When I first read it, I was twenty years old and still reeling from my own first exposure to international travel, a relatively tame semester in suburban Scotland. I was gripped by the notion that travel could confer the same eagle-eyed clarity that Thompson seemed to enjoy, and I told myself that I would go abroad again as soon as possible.

But I never did, and ten years later, I found myself still wondering about that act of transformation, about how you could leave home one day and come back with a clearer understanding of your own world and your place in it.

So a couple of months before purchasing my Colombia ticket, I dug up all of Thompson’s South American reportage from a dusty microfiche archive of the National Observer. In total, there are eighteen stories. A few were reprinted in Thompson’s 1979 collection, The Great Shark Hunt, but most have been out of print for more than fifty years. The majority of the articles revolve around the Cold War drama of American foreign policy, the triumphs and travails of a Kennedy-era idealism that sought to remake South America in its own capitalist image. Others offer “slice of life” portraits of societies colored by corruption, violence, and political intrigue. The stories offer glimmers of the “gonzo” style that Thompson would later develop. They’re gritty and shrewd, and most impressively, they’re keyed into a number of social issues that still affect the continent today.

Reading Thompson’s Observer stories and letters from the continent, I got the impression of a bright and driven young writer—a bit of a hell-raiser, sure, but one with a clear voice and an emerging interest in democracy and world affairs. Thompson the vagabond reporter came off as worldly and inquisitive, with a lightning-quick wit and a budding sense of injustice. It was, in many ways, a template for the sort of writer—for the sort of person—I wanted to be. Poring over the columns of old newsprint, my face lit up by the glow of the microfiche reader, I found it impossible not to layer my own voice over Thompson’s, not to feel a sense of kinship. Both of us had come out of flyover country and settled in the American West. We shared a love of the outdoors and a nascent interest in politics. And we were, it seemed to me, both at a similar place in our lives. I too felt the now-or-never urgency that the young Thompson had described, that looming sense of a “last chance to do something big and bad, come to grips with the basic wildness.”

But instead of traipsing around South America, I had spent my twenties settled into a classroom, a desk job, and a premature marriage. I looked with a kind of wistful admiration to the younger and hungrier Thompson whom no one seemed to know—much, I suppose, as Thompson had once looked to Hemingway, Faulkner, and his other literary heroes. Something in South America changed Hunter Thompson, and I wanted to know what it was, to figure out how the experience of a foreign culture had so altered his relationship with his own. In truth, I wanted some of that transformation for myself. At twenty-five, Thompson returned home from South America with a new understanding of journalism, injustice, and the American Dream. I, on the other hand, was staring down the barrel of my thirties with two useless degrees, no job, and a failed marriage, the ink on the divorce papers still wet. And I didn’t understand a damn thing.

My e-mail exchange with Sky paraphrased all of this, though I played down my existential angst about transformation, the American Dream, and so forth. My plan, I told him, was to retrace Thompson’s route across the continent, and this is what explained my offbeat itinerary. Barranquilla—hot, bland, or otherwise—was my starting point.

Sky was intrigued. “I am totally game to join you for a leg or two of your journey,” he offered. Would I have any interest in a partner for the first few weeks of the trip? Someone who knew his way around Colombia and spoke far better Spanish than my rudimentary child-speak?

Sí, I told him, absolutamente.

So there we were a few months later, in Barranquilla, getting to know each other at the Colombian equivalent of a TGI Fridays.

“Yep,” Sky said again, setting down his beer. “This is easily one of the ugliest cities I have ever seen.”

I couldn’t disagree. My taxi ride from the airport had given me my first real glimpse of Latin American urban poverty, a suffocation of sheet-metal shanties that seemed to characterize much of the city’s outskirts. Traffic in Barranquilla was a lawless, laneless contest of cabs, donkeys, and moto-taxis, all competing against the gaudily painted, repurposed school buses that served as mass transit. The shopping district surrounding our hotel seemed inoffensive enough—densely packed avenues of concrete, neon, and litter—but I’d come through several seedier sectors on my way into town, passing whole blocks of morning-time drinkers and what looked to be an impressive number of whorehouses.

“So all of this out here,” I asked, gesturing at the tired palm trees and mausoleum-like office buildings, “this is not typical of a Colombian metro?”

“Man, not at all.” Sky shook his head. “Much more drab than Medellín or Cartagena. Colombians are actually super-passionate about their architecture. Art Deco is big. There’s a ton of colonial preservation. But this place?” He shrugged. “I don’t know, dude.”

Sky gave a quick side-nod toward an adjacent table, and I looked over to where a trio of cute uniformed nurses sat, chatting over their cocktails in clipped Caribbean Spanish. He leaned over his place mat conspiratorially.

“On the other hand,” he said, “there are things that don’t change no matter where you go in Colombia.” He sat back in his chair and grinned slightly, raising his bottle in a mock toast. “At least the women of Barranquilla are still beautiful.” Then he took a long swig and exhaled in satisfaction. “Hey, did you know this is Shakira’s hometown?”

Sky was a tall, tanned thirty-year-old with a goatee and the kind of nondescript, close-cropped haircut that’s justifiably popular in equatorial climates. More often than not, he wore a camera around his neck and a leather satchel over one shoulder, heavy with lenses and other tools of his trade. Over beers that afternoon, he regaled me with stories of his time on the continent, waxing romantic about his fondness for Colombia, which in large part seemed to stem from his fondness for Colombian women. Sky was clearly a bit of a playboy, a good-natured soldier-of-fortune type who could segue onto the subject of women from seemingly any unrelated topic. He also kept up with my beer consumption, which I admired, and he seemed just as passionate about South American politics and social movements as he was about the Shakira look-alikes coming in and out of the bar. I liked him instantly.

“So our first stop is Guajira, then?” Sky asked as the bartender brought another round.

“La Guajira,” I confirmed. “The land of the Wayuu, where Thompson first touched down in May of ’62.”

I had mailed Sky photocopies of Thompson’s Observer stories, including his first article from the continent, entitled “A Footloose American in a Smugglers’ Den.” The piece opens on Thompson as he disembarks from the bootlegger’s boat in a tiny village at the tip of the peninsula. He had managed to hitch the ride there from the Dutch island of Aruba, about ninety miles out to sea, where he’d stopped en route to the continent after visiting friends in Puerto Rico. From the Observer story, Sky and I had gleaned what little we knew about Guajira: (a) that it was a desert, and (b) that it consisted largely of reservation land for Colombia’s indigenous Wayuu tribe. Some cursory Internet searching hadn’t revealed much more. Like many Latin American countries, the Colombia of the Internet reflects mostly those areas of interest to visiting tourists, and Guajira isn’t a region that sees a lot of gringo traffic—or any kind of traffic, really, since the whole peninsula is largely without roads.

“The problem is,” Sky said, “I don’t know any smugglers with boats. So how are you supposing we get out there?”

I unfolded a map that, thankfully, I’d been using as a bookmark. “We can take a bus as far as Riohacha,” I said, pointing to a town some 125 miles east of Barranquilla. Riohacha is the capital of the La Guajira department (the Colombian equivalent of a state) and effectively the gateway to the peninsula. Near it on the map was a small blue icon of a beach umbrella, indicating la playa. Where there was la playa, I figured, there would be some kind of tourism infrastructure. From Riohacha, then, I hoped we could rent a truck or some other sort of off-road conveyance.

Sky laughed. “That simple, huh? Then we just tear off into the desert, full speed ahead?”

I nodded.

“And what are we looking for exactly?”

I shrugged. “Stories, I guess. Adventure. Ghosts.”

We both laughed at how little we’d planned anything beyond that moment. At least in this, I thought, we had something in common with Thompson. When the nurses at the neighboring table got up to leave, Sky’s eyes followed them to the door.

“You know what they call speeding in Colombia?” he asked, turning back to me. “Ir a toda mierda, which basically means ‘going full shit.’ ”

I laughed again and finished my beer. The two of us stayed at the pub for a couple more hours that night, poring over the map and sketching back-of-the-napkin itineraries beneath posters of scantily clad Aguila beer models. By the time we teetered back to our hotel, feeling chummy and intrepid, my backpack was waiting for me in the room. On one of the plastic clasps, the airline had tied a short note. Buen viaje y buena suerte, it read. So long and good luck.

II

“It’s good that you should see a Colombian mall,” Sky said the next morning as we nursed our hangovers with fried eggs and guava juice. “They’re no different than American malls, really, but Colombians love them because they combine two of their favorite things: shopping and air-conditioning.”

The Muzak and fake foliage of the Portal del Prado shopping center wasn’t the rugged, romantic setting I’d pictured for my first full day in South America, but simply “going full shit” into the wilds proved more difficult than I’d envisioned. There were errands to run and bus tickets to buy, and in Colombia, these kinds of seemingly straightforward tasks can sometimes occupy one’s entire day. Simply put, America’s quintessentially Protestant emphasis on efficiency has never gained much of a foothold in Latin America, where any number of commonplace tasks and routines can seem needlessly swaddled in layers of tail-chasing and bizarre, paradoxical frustrations.

Consider the phenomenon of Colombian cell phones. Before setting out for Guajira, Sky and I needed to gather a few things: some nonperishable food, cash, batteries, a couple of bags of “goodwill” candy for any kids we met along the way. But most important and time-consuming was the task of acquiring a couple of cell phones. It had never occurred to me that I might carry a cell in South America. For starters, I was accustomed to a messy system of contracts, carriers, and expensive plans back home. Moreover, I hadn’t expected to find much service outside of the major cities. So the ubiquity of cell phones and cellular coverage in South America was the first of many misconceptions about the developing world that would evaporate for me in the coming months.

This is not to say that Colombian cell phone usage makes any sense. Dirt-cheap and available on every street corner, most Colombian cells operate on a counterintuitive arrangement in which minutes are prepaid and incoming calls are free. The result of this, Sky explained on our way to the mall, is a Kafka-esque scenario in which everyone owns a cell phone but no one ever has any minutes. So rather than waste their own, most callers will simply dial their intended target, then wait for a single ring before hanging up, hoping that the recipient will call back on his or her own dime. Which, for lack of minutes, no one ever does. Consequently, the streets of most Colombian towns are crowded with vendors charging customers to use fleets of non-depleted cell phones, which they keep tied to chains like pens at the bank. In even the smallest Colombian villa

ges, you can’t throw a rock without hitting a sign that advertises these minutos, posted in corner-store bodegas, on street carts, and even in private homes.

But we didn’t want to rely on minutos, and we figured there’d be times when we’d need to call each other, so we squared away our phone situation at Portal del Prado, enjoying some Arctic air-conditioning in the process. Sky’s Spanish was vastly superior to mine, so he mostly handled the transaction, flirting mercilessly with the round-eyed, tube-topped attendant at the kiosk. Funny, I thought, how easy it is to recognize playful innuendo, even when you’re fighting to understand the language.

The rest of our supplies we picked up at the Colombian equivalent of a Walmart anchoring one end of the mall. Unlike American big-box stores, however, this particular retailer employed several conspicuously armed security guards, which I learned when one of them chased me down to ask gruffly that I check my backpack in a locker. From the short-barreled rifle hanging at his side, I guessed that gringos with illicit backpacks were the least of his potential problems. So there’s at least one difference between American and Colombian malls, I thought. In Colombia, the mall cops get to carry guns.

We were further delayed at the bus terminal, where a smooth-talking driver duped us into leaving Barranquilla on the local rather than the express, which meant stopping for a pickup at every no-name village along the way. It’s an easy mistake to make in Colombia, where every shifty-eyed counter agent will assure you that his is the only nonstop route. We stuck out the bus ride for several hours, covering all of seventy miles before switching at another terminal to a puerta-a-puerta—a “door-to-door” shuttle van that carries a dozen passengers for a few pesos more than bus fare. Our particular conversion van was packed with middle-aged men and smelled faintly of diesel, and when it finally pulled away from the station, it was clear we had zero chance of reaching Riohacha before nightfall. But at least Barranquilla was in the rearview mirror, and the rest of the continent spread out in front of us like a dashboard map.

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America