- Home

- Brian Kevin

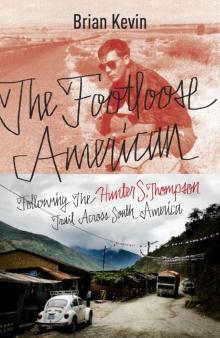

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America Page 9

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America Read online

Page 9

It wouldn’t be fair to blame everything that happened next on Sky’s Casanova gallantry—or on the mesmeric curves of his Honda heartthrob—but both of them got us off to a late start the next morning. While Ivan and I stood holding our bags, Sky put us off for two hours while he ran around town, arranging to have flowers delivered and a song dedicated to his crush on Ricardo’s radio station. I tried to keep the wait in perspective: after five days in Honda, if one flurry of last-ditch courtship was the price of a ticket out of town, then I was happy to pay it.

It was past noon by the time we lifted anchor, but the day was cool and clear. All three of us were in high spirits, never mind the delay. Ivan brought along a boy he called Sardino to help him man the boat, and Sky and I laughed while we answered Sardino’s wide-eyed questions about los estados unidos. The tiny motorboat bucked like a rodeo mule as we plowed through Honda’s rapids, and by the time we reached the city limits, we were all soaked and a little bit giddy.

A few hours upstream, we stopped for gas at a riverside village called Ambalema. Near the docks was a ramshackle cerveza stand, and the three of us sat down for beers while Sardino went off to fill a half dozen gas canisters. Ivan pointed across the water to the far shore.

“On that side of the river was my grandfather’s farm once,” he said, “before the narcotraficantes came in the 1990s.”

This whole stretch of river was effectively a war zone then, Ivan said, and as we slaked our thirst, he told us candidly about the bad old days of the ’90s and beyond. Industry might have abandoned the Magdalena around the time of Thompson’s journey, but the narcotraffickers who came to prominence afterward still saw the river’s value as a transportation corridor. One of Pablo Escobar’s closest captains controlled this stretch for a time, Ivan explained. When he died, there were rumors of money and weapons hidden around Ivan’s grandfather’s farm. Some pretty unsavory types passed through, searching for loot that was never found. Then the paramilitaries came in, and they picked up where the narcos left off, taking over abandoned farms and moving money and drugs up- and downriver. Ivan had an uncle who hung on to the family farm for as long as he could, until the only people left in the area, Ivan said, “were all full of nerves and delusions.” Finally, the uncle gave in and sold the farm cheap.

The bartender chimed in as he passed out another round, remembering a time when he wouldn’t have crossed the river for fear of his life. Ivan nodded. President Uribe had gotten rid of the narcotraffickers, he said admiringly, and anyone who criticized the US–Colombia alliance didn’t understand the difference this had made in the lives of many rural Colombians. Both Ivan and the bartender had enthusiastically supported the amendment permitting Uribe’s second term, and had it been possible, they said, they would have given him a third term too.

Our couple of beers turned into three or four, and the bartender brought over a complimentary round of aguardiente. Ivan bought a beer for Sardino, who laughed and tried to tell us he was seventeen, then admitted to being fifteen, then twelve. When I asked Ivan why we hadn’t encountered any of the vicious insects that Thompson had described so vividly, he grinned and told us that Uribe had gotten rid of those, too. We laughed and traded shots. All around us, the peaks of the Cordillera Oriental rose up amber against the sky.

By the time we got back on the water, everyone was feeling great. Sky’s wooing and our impromptu happy hour had put us hours behind, so Ivan cranked the outboard, and we sped upriver in the fading sunlight, enjoying the encroaching mountain scenery. At our approach, the elegant garzas rose up from their perches among the reeds and came to rest on the nearby branches, drifting upward with all the grace and urgency of tissue paper caught in the wind.

We were fifteen miles shy of Girardot when Ivan’s engine suddenly made a sound like something out of a blacksmith’s workshop, and the boat went into a full-tilt clockwise spin. Sardino scrambled to kill the motor. Sky and I reflexively grabbed the oars. Mine barely skimmed the surface of the water as the lancha leaned hard to starboard, listing skyward at a forty-five-degree angle. Ivan grunted loudly at the wheel as he tried to straighten us out.

“Towards the shore!” he yelled. As the boat slowly regained its equilibrium, Sky and I paddled hard across the current, straining to keep the fast-moving water from sweeping us back downstream.

After a tense few minutes, we dropped anchor next to a rocky beach, where everyone simply sat still for a while, catching their breath. A transom bracket had cracked, leaving the outboard motor dangling uselessly from the stern. As Ivan and Sardino examined the damage, Sky and I clambered ashore, shaking off the river spray and our aguardiente fog. He could fix it with rope, Ivan said eventually, but our speed was going to suffer something fierce. Late as it was, there was no way to make Girardot by nightfall.

The map suggested a small village nearby, but no one could remember whether we’d passed it already, so we motored a short distance upstream, keeping our eyes on the banks. Instead of a village, we came to a small farm plot on the east side of the river, where a somber papaya farmer and his family were sitting outside in the encroaching dusk. They eyeballed us silently as we approached and dropped anchor. None of them seemed to know quite what to make of the ragtag crew disembarking from this tiny boat. Sky and I nodded hello, and Sardino offered a tentative wave.

Ivan waded ashore and consulted with the farmer for a few minutes, then came back to say we’d been offered food and hammocks for the night. We all clambered out of the boat and shook hands, changing into dry clothes and settling in with the family on a set of wooden benches and mismatched patio furniture.

The farmer’s wife brought us coffee and plates of pollo con arroz, and we tried to make chitchat while we ate. Our host was a large, impassive man, and heavily inked. On one arm I saw a graceful Pegasus taking flight; on the other was a hairy and grotesquely detailed spider. He’d been in the Colombian military once, he explained slowly, but now he raised papayas here on the Magdalena and drove a cab a few days a week in Girardot for extra cash. A handful of related families lived there on his farm, a sort of cooperativa. When Sky asked why he left the military, he was quiet for a moment, chewing on a forkful of rice. “Violaciones de derechos humanos,” he finally muttered. Human-rights violations. And that pretty much put an end to that conversation.

Still, he and his family were kind to let us stay. We could sputter into Girardot in the morning, we decided, where a friend of Ivan’s could retrieve him, Sardino, and the boat. So we settled into our hammocks beneath the stars, the gurgling river within earshot. Around midnight, the skies suddenly opened up with a tropical storm, and we all roused sleepily to settle inside on the farmer’s dirt floor. No one thought much about the boat anchored up along shore, covered only partially by a fiberglass awning and filling slowly with rainwater.

The next morning, I learned what it was like to see the river as an obstacle, robbed of its romance. The sunrise sight of Ivan’s submerged boat was as surreal as anything from Márquez, and twice as disquieting as Thompson’s gruesome bugs. I woke up and walked outside shortly after Ivan, and I found him just standing on the lawn, looking out sadly at the river, from which only the rear half of his small boat was protruding. The rain was still coming down hard, and that part was disappearing fast. Ivan and I looked at each other for just a moment. Then he ran toward the river as I turned back to wake Sky and the others.

Within minutes, I was fully immersed in the dark swell of the Magdalena River, breath held and heaving against the fiberglass hull of Ivan’s half-submerged boat. Somewhere to my right was Ivan, and I could feel the force of him as we strained against the current to keep his lancha from capsizing completely. The shouts of the men onshore sounded thin beneath the gasoline-contaminated water. My nostrils stung. My sinuses burned.

The irony of the situation struck me while my hands blindly scoured the river bottom for one of the full gas canisters we’d had on board. Sky and I had set out upon the Magdalena hoping in part to gau

ge its ecological health. Now here we were, just miles from our terminus, leaking fuel into it at an alarming rate. When I came up for air, I saw my reflection, wavering and distorted on the water’s oily surface. I heard the swish of the rain through the long-leafed palms. Then I shut my eyes and plunged back underwater.

Don’t think of this as a catastrophe, I told myself. Think of it as a rite of passage. Think of it as a baptism.

We worked for hours to pull the lancha up from the current—Sky and the farmers all heaving at ropes, Ivan and I straining underwater against the hull. It was early afternoon before we recovered enough of the boat to start bailing. Sky’s hands were lacerated, and I reeked of petroleum.

Ivan, however, kept his cool throughout, and as I watched him take charge of the situation that day, I felt myself coming to an understanding about the Magdalena and its people. As was probably true in both Márquez’s day and Thompson’s, most magdalenos seem to regard the river simply as an entity in flux, something to be enjoyed one day and struggled against the next. For better or for worse, life along the Magdalena just seems to foster more stubborn will than it does romantic appreciation. It’s an adaptive mind-set, and the ecosystem occasionally suffers for it, but it’s an outlook that fortifies people, that helps them to function in a sometimes violent and capricious society.

Hours later, a friend of Ivan’s arrived with a pickup, and Sky and I slumped into the truck bed with Sardino, riding in defeat the last ten miles into Girardot. For the second time in two days I found myself identifying with Thompson’s bleak disposition—specifically with his river-weary assertion that “if I ever get to Bogotá, I may never leave.” He wrote nothing at all about the end of his journey on the Magdalena River, but somehow I imagined that it was more jubilant than ours.

Girardot itself looked bland as we drove into town, passing big-box stores and cheap-looking resorts for vacationing Bogotans. We parted too hastily with Ivan at a downtown intersection, grateful for the time we’d shared but feeling awkward about the damage to his boat. By then, we’d all run out of things to say anyway, and Ivan smiled with resignation as we told him good-bye—a smile that said, Well, I guess I got myself into this. Sardino was wearing a shirt that I’d loaned him after our battle with the sunken boat. It had been my grandfather’s, but I didn’t have the heart to ask for it back.

That evening, Sky and I stood on a railroad bridge, too tired to drink the celebratory champagne we’d bought in Honda. Beside us was a historic depot that once welcomed steamboat passengers to board the seventy-five-mile train ride to Bogotá. We looked away from the bridge to the south, where the Magdalena ascended another 250 miles to its source in the Colombian Massif. I imagined skimming the surface of the water for the length of that trip, hovering above it as it grew fast and shallow in the Andes, then watching as the river reclaimed its youth, dwindling away into a thin mountain stream, a trickle, and then nothing.

CHAPTER THREE

Sex, Violence, and Golf

Somewhere below us, in the narrow streets that are lined by the white adobe blockhouses of the urban peasantry, a strange hail was rattling on the roofs.

—National Observer, August 19, 1963

I

Sky and I passed our remaining time together riding out a few additional small crises. By sunset in Girardot, we both felt sick with headaches and chills. I chalked it up to having spent our morning submerged in a cold and angry river, and we spent the night wallowing in our motel room, eating pizza and watching a Jeff Bridges movie that turned out to be about a sinking boat.

By morning, I’d made a full recovery, but Sky looked rough—pale and jittery, with bags beneath his eyes. On the short bus trip into Bogotá, he coughed and groaned, too tired and achy even to point out the attractive women seated nearby.

“I had better not have the swine flu,” he croaked, slouched against the Plexiglas window. “I have a plane to catch, and if they don’t let me on, I’m going to be in real trouble.”

It’s hard to remember now, but at the time, swine flu was the international apocalyptic disease du jour, and we’d been hearing about it regularly since Barranquilla. Former president Uribe had been diagnosed with the H1N1 virus just three weeks earlier, after falling ill during the same UNASUR conference we’d watched on the bus. Since then, we’d heard rumors that Colombia’s whole cabinet was afflicted. Then it was the whole legislature. It was a brutal pandemic, warned the sporadic TV news we’d seen along the way, and it was sweeping unstoppably across Bogotá. But we didn’t put much stock in such reports, since Colombian media is in no way above American-cable-news–style sensationalism, and since ratings-wise, contagious respiratory diseases rank right up there with earthquakes and blond-girl kidnappings.

Our bus shuddered up the steep grades into Colombia’s high-mountain capital, and by the time we found a cheap hostel in the colonial district, Sky was bleary-eyed and incoherent. I was helping him carry his bags into our dorm room when we both noticed the large-print poster stapled to the door:

SWINE FLU IS DANGEROUS AND HIGHLY CONTAGIOUS! SYMPTOMS INCLUDE SUDDEN ONSET OF FEVER, CHILLS, COUGH, SORE THROAT, CONGESTION, AND BODY ACHES.

“Well, shit,” Sky said slowly, sounding a bit dazed. His face had lost its remaining traces of color. “Dude, am I going to die?”

I tried to sound upbeat. “Probably not,” I said. But the symptoms did seem to line up, and I imagined he was right about the airlines taking swine flu seriously.

So we opted to play it safe, and within a few hours of arriving in the cold, gray capital, we were standing outside of an even colder, grayer hospital, watching ambulances fight their way up the crowded street toward the ER.

I have never cared much for hospitals. I grew up just down the street from one, and looking back, it seems like someone I knew was always in it—an uncle following a stroke, my dad with a kidney stone, a classmate after a near-fatal asthma attack. The hospital’s boxy brick exterior loomed oppressively over our neighborhood, and it made for a steady stream of sad-looking people pacing up and down the block. Today, as a perennially uninsured adult, I’ve come to think of hospitals as strongholds of disease rather than places where I might receive treatment for one.

That everyone pacing outside Bogotá’s hospital wore a surgical mask only heightened my unease. This is a creepy thing to see in any town—a crowd full of half faces, noses and mouths hidden behind paper muzzles of pale green. I felt sick just looking at the place.

Sky was already a goner, I decided, but there was still hope for me. If I hadn’t already contracted swine flu from a month of close quarters with the photographer, I would sure as hell pick it up in there. I grasped Sky’s shoulders in what I hoped was a brotherly manner and gave him an encouraging send-off.

“Best of luck in there, buddy. I’ll be in the café across the street.”

If you must seek medical treatment abroad, you can do a lot worse than Colombia. Statistically speaking, Sky was just one of 15,000 or so foreign visitors who see the inside of a Colombian medical facility each year, and the great majority of these actually schedule their own appointments. Medical tourism is big business in Colombia, where the expertise of doctors is high and the costs (compared with Europe and the United States) are staggeringly low. A hip replacement that might set you back $50,000 in the United States costs only around $9,000 in Colombia. A gastric-bypass surgery in Colombia runs around $15,000, compared with ten times that in the States. According to Colombia’s Trade Ministry, about half the country’s medical tourists come for either bypasses or heart surgery.

Of course, Colombia is probably more famous for the 10 percent who come seeking plastic surgery. It is this sector, in any case, that the country’s tourism industry seems most eager to promote. During my time in Bogotá, headlines there trumpeted the construction of a brand-new cosmetic tourism facility on the city’s glitzy north side. When completed, the $19 million Bosque Beauty Garden will be Colombia’s first hotel/surgical center, appealing to th

ose who seek both lofted luxury and lifted brows.

That plastic surgery is popular in metro Colombia is not a fact that requires much support from government stats or medical journals. In certain neighborhoods, the signs and billboards for boob jobs seem almost to outnumber the total number of available boobs. And if the advertising doesn’t tip you off, the suspiciously high number of suspiciously round buttocks probably will. Colombians take beauty and body image very seriously, and it’s their proud reputation for superficiality that attracts so many nose-job nomads. Sky had actually explained this to me during our very first meeting back in Barranquilla, during an opening soliloquy about the virtues of Colombian women, and I’d seen plenty of evidence since. Yes, there were the ubiquitous ads for plastic surgery, but there was also the country’s conspicuous obsession with beauty pageants. I’d flipped past half a dozen of them on motel TVs and seen pictures of winners splayed across every supermarket newsstand we’d run across. On Mompós, we’d caught the tail end of a parade dedicated to the town’s reinas—pageant-winning “princesses,” all dolled up like child victims of reality-TV moms and carted around on streamer-lined floats. Even as I settled into the café across the street from the hospital, it was hard not to notice how explicitly sexualized were the soda posters and the ice-cream ads—collagened lips pressed against Coke bottles, buxom young women simulating fellatio on their cones.

Even fifty years ago, Thompson had noted approvingly that Colombia had a “wholly different sexual climate” from the United States. It was, in fact, one of the things he’d most admired about the country’s Caribbean coast. In his letters, he writes admiringly about “the fine, lusty tension in the air” in what he’d seen so far of Latin America. In general, Thompson’s letters from the continent exhibit a healthy libido. He writes candidly, for instance, of having visited a brothel in Barranquilla, but he also seems to have a sociological interest in sex that transcends the mere chasing of tail. With anthropological detail, his letters describe the relationships among Colombian men, their formal prostitutes, and their informal mistresses. Then as now, prostitution was legal, but its legality conferred none of the borderline respectability enjoyed today by sex workers in progressive enclaves like, say, the Netherlands. It was one thing to legally patronize a working girl, Thompson explains, but quite another to be seen in public with one. The mistresses, meanwhile, were considered “nice girls”—debutantes who kept their bedroom exploits clandestine. Specimens from either group, Thompson told an editor, “will knock your eyes out.”

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America