- Home

- Brian Kevin

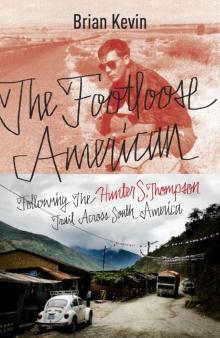

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America Page 19

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America Read online

Page 19

The overnight bus from Lima to Cusco departs in the evening and climbs 15,000 feet in the darkness. I stared out the window at the central Andean highlands until my eyes hurt, thinking about the mountains back in Montana and tracking the taillights of the buses ahead. Sometimes I’d spot them an hour or more up the road, ascending a switchback on the opposite side of a gorge, faint red dots bobbing and gliding through the night like lit cigarettes. I slept as best I could, and in the morning, the high-country sunrise burned slate-gray and pink.

The bus route led through roughshod mining towns clinging to the sides of mountains and through valleys filled with sugarcane plantations, where every stooped laborer wore the patterned alpaca poncho of the Quechua-speaking highlanders. This was the other Peru, the one that Thompson said was as different from Lima as Manhattan was from Appalachia. Geography is culture, of course, and Peru sits at a crossroads of three disparate South American ecosystems. The criollo cultural elites make up a majority in the coastal departments (la costa), but almost half of Peru’s population is of pure Amerindian stock, and these indigenous descendants overwhelmingly occupy the Amazon regions (la selva) and the thin air of the Andes (la sierra). In these inland provinces, poverty rates are a few clicks higher and literacy rates substantially lower. Lima feels far away indeed, and antiestablishment messages tend to resonate here, which is one reason why Ollanta Humala won handily in thirteen of the fourteen Peruvian departments that lack an ocean view.

Back in Thompson’s day, support for APRA was also heavy in la sierra, but with one key difference: literacy and ID requirements kept between 65 percent and 80 percent of the largely Quechua population from voting. And this kind of indigenous marginalization was at the heart of Thompson’s remaining article on Peru, entitled “The Inca of the Andes: He Haunts the Ruins of His Once-Great Empire.” It’s a piece that paints a pretty brutal picture of the indigenous experience in the Andes during the Alliance for Progress era. It opens on downtown Cusco, where Thompson says that a Quechua drifter on the street was “as sad and hopeless a specimen as ever walked in misery. Sick, dirty, barefoot, wrapped in rags, and chewing narcotic coca leaves to dull the pain of reality.” In the article’s opening lines, Thompson describes the waiters scurrying to close the blinds in the lounge of his comfortable Cusco hotel, so that the tourists inside won’t be bothered by the “Indian beggars” staring in from the other side of the glass.

Reading through his articles and letters, it seems to me that Thompson was particularly put off by indigenous poverty in South America. As evenhandedly as he described the Wayuu back in Guajira, he seemed to write with genuine surprise and revulsion about their squalid living conditions, about the food that was “unfit for dogs.” In his letters, he gripes that “the whole continent is covered in Indian shit” and regularly complains of having to “carry a truncheon to ward off the citizenry.” “From Bogota south,” he wrote in the Observer, “the Andean cities are overrun with Indian beggars who have no qualms about lying on a downtown sidewalk and grabbing at the legs of any passers-by who look prosperous.”

What to make of Thompson’s outsize discomfort? To put it in context, it helps to remember that in 1962, what we then called the Third World hadn’t really come into Americans’ living rooms yet. If John Q. Public had any idea of what life looked like for an Andean farmer or a child in sub-Saharan Africa, he sure didn’t get it from Alan Sader or Sally Struthers. The global proliferation of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) didn’t kick off in earnest until the 1970s, and up until then, most of the hardest-luck corners of the world were still largely the domain of missionaries. If Thompson at first seemed shell-shocked or even derisive about the extent of Andean poverty, it could be because very little in his experience would have prepared him for so many abject faces staring in through the windows—or the callousness with which the blinds were pulled.

Thompson pitched “He Haunts the Ruins” not long after leaving Cusco, but he was back in the United States by the time he finished writing the story, in the early summer of 1963. By then, he’d had some distance from the Andes, and he’d also passed through Bolivia, where the Amerindian population had voting rights and an increasingly prominent place in civil society. With the benefit of hindsight, Thompson took a more nuanced view of the Quechuas’ plight, explaining how the active disenfranchisement of the indigenous population worked to benefit those in power. “Once the Indian begins voting,” he wrote, “he has little common cause with large landowning or industrial interests. Thus the best hope for the status quo is to keep the Indian ignorant, sick, poverty-stricken, and politically impotent.” By the end of the article, Thompson comes off as a strong advocate for indigenous empowerment.

Whether the indigenous descendants of the Incas are any more empowered today is up to debate. Voting is compulsory now, so even the most isolated Quechua-speaking family is at least that much more involved in the democratic process. Native Andeans are also a lot more “serviced” than in 1962. Over the last few decades, Peru in general has become a nexus of the booming NGO and nonprofit industry, and la sierra is the sector’s major focus. One British think tank published a report nicknaming Peru “The Kingdom of the NGO,” and the country’s International Cooperation Agency lists more than three thousand such organizations on the books. A couple hundred of these are based in the Department of Cusco, home to the Sacred Valley, the historic heart of the Incas’ “once-great empire.” Today, the only thing that attracts more foreigners to the Sacred Valley than the NGO sphere is that great consecrated citadel of international tourism itself, Machu Picchu.

I spent my first few days around Cusco just drifting through the NGO orbit. Needless to say, the city is a historic marvel, very worthy of its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The buildings surrounding the central Plaza de Armas are stoic masterpieces of stone archways and red tile roofs, and a person strolling across it can look up to see no fewer than six picturesque church steeples punctuating the skyline. Although the Spanish razed most of the Incas’ former capital and built their city over its foundations, there are still any number of dramatic stone ruins found within biking distance of the city limits. Cusco is also arguably the beating heart of the Gringo Trail, packed year-round with multinational tourists of every socioeconomic stripe, and the city center is lousy with the restaurants, hotels, and curio shops that cater to them. Hopelessly unavoidable around the plaza are the gregarious reps for Cusco’s dueling parlors—pizza and massage—who seem to assault passersby with flyers every six or eight yards.

Around the corner from all this is the quiet second-floor office of Asociación ANDES, also known as the Quechua-Aymara Association for Sustainable Livelihoods. I was met there one afternoon by the organization’s director, Dr. Alejandro Argumedo, a Peruvian-born and Canadian-educated agronomist who agreed to talk with me about the contemporary issues facing indigenous Peruvians.

“Sure, wherever you go around here, there’s an NGO working,” Argumedo told me with a smile and a shrug. He’s a mop-topped ethnic Quechua in his forties, with wire-rimmed glasses and the habit of talking with his hands that’s common among those who regularly switch among languages. Argumedo speaks English, Spanish, and Quechua fluently, and he understands a little Aymara, the mother tongue of Peru’s minority mountain indigenous group, cousins to the Quechua and one of the main conquered peoples of the Incas.

“The problem,” Argumedo said, “is that too many of them have these ultra-specific mission statements, these little feudal spaces where they only ever take on micro projects.” I thought of posters I’d seen during my first walk around Cusco, seeking “voluntourists” for projects that revolved around alpaca textile-weaving, building passive-solar greenhouses for mountain villagers, and teaching digital photography to street children. “Then suddenly they leave, and eventually, it’s all gone.”

Asociación ANDES tries to break out of that mold, he explained. As far as Argumedo is concerned, the baseline threat to indigenous Andeans today isn

’t simple exploitation or illiteracy or political oppression, but the far more subtle loss of biocultural resources that enable a way of life. Alleviating poverty, promoting civic engagement, putting food on the table, and preventing families from migrating into city slums—all of these things hinge upon making an agrarian lifestyle in the Andes as viable as possible. To that end, said Argumedo, he and his colleagues work to defend indigenous rights over seed patents, cushion the agricultural blows of climate change, and alter macroeconomic policies that reward the cultivation of export crops at the expense of subsistence farming. In particular, ANDES works closely with the surrounding mountain communities to facilitate the kind of communal land structures that allow for diverse agriculture in a landscape so breathtakingly vertical.

“Fruit grows at lower elevations,” Argumedo explained, “grains in the middle, and tubers on top.” He stacked his hands one above the other, like rungs on a ladder. “If you only own one plot at one elevation, then you’re kind of out of luck. That’s why this Andean environment has always necessitated cooperation.”

Thompson actually made note of this collective agricultural model in a memo to his editor, accompanying some photos of Quechua farmers at work: “The farms around the village are run on the old Inca communal system (communist, some call it), wherein the families help each other work the land and share the profits.” The parenthetical seems significant, especially when considered alongside a quote from a government agricultural adviser in “He Haunts the Ruins,” a technocrat frustrated that “the Indian lives almost entirely outside the money economy.” I asked Argumedo, Is there some element of nostalgia at work here? I mean, why work to maintain these traditional lifestyles rather than helping the Quechua assimilate into a modern consumer society?

“Look, this isn’t about some romantic cultural heritage,” he said, sipping from a mug of heavily sweetened coffee. “Food costs are soaring around the world, thanks to a number of factors—oil prices, changing weather patterns, increased demand.” He ticked off the items on his fingers, one at a time. “In Peru, we already import forty-five percent of our grain. A lot of our potatoes are imported from Canada. I mean, Canada? We’re the homeland of the potato!”

He gestured to a few posters on the wall, showing different potato varieties in Day-Glo shades of red, purple, and orange. They were weirdly beautiful, like crosses between seed-catalog centerfolds and Warhol canvases.

“We can’t afford to do this forever,” he said, “and as we get closer to peak oil, our food transport prices are going to skyrocket. So this isn’t a cultural preservation issue. It’s about how to sustain ourselves right now, and not just us, but the entire country.”

There was an appealing irony, I thought—that Peru’s future prosperity might rely upon the very pre-Columbian lifestyles that its ruling class had been trying to squelch, or at least marginalize, ever since Pizarro first drew a sword against the Incas.

“So do people in Lima see it this way?” I asked. “Policymakers, potential donors?”

Sometimes, he acknowledged. But there was also a kind of disconnect between the mountains and the coast, even a disdain for what had always been viewed as a backward way of life. I had noticed this, I said, and I compared Peru’s social tensions to the culture war between “red states” and “blue states” back home.

“I’ve lived in Colombia and Ecuador, and I regularly work in Brazil and Argentina,” he said, setting down his coffee mug to free up his hands, “but there is no question that Peru is the place where animosity and distrust for indigenous people are the strongest.”

“Why is that?” I asked, and the agronomist leaned back in his chair and showed me his palms.

“I think people tend to project whatever it is they want to be,” he said, “and then they try not to see anything else. For instance, you see these advertisements around Cusco with the blond woman drinking Inka Cola.” I had indeed noticed the poster ads for Peru’s popular homegrown soft drink. Argumedo laughed. “Man, there is nobody around here who looks like that! Maybe this is the same reason a lot of people voted for Kuczynski,” he said, referring to the gringo economist with the dancing guinea pig and Wisconsinite wife. “People just ask themselves, ‘What is it that I want to be?’ Well, white-ish! Prosperous!

“The thing is, people who think that way don’t always want to see indigenous people. But we’re here, and we need to be seen.”

I thought of the closing line from Thompson’s story: “The Indians are still outside the windows, and … they are getting tired of having the blinds pulled on them.”

Argumedo shrugged again, then slapped his hands on his knees, in a way that said he’d had this conversation many times before, and this was the only bottom line he’d come up with. “If this attitude seems very entrenched here,” he said, “it is because we were at the epicenter of colonization. And everyone knows that the people who get hit hardest are always the ones at the epicenter.”

V

My last stop in Peru was Machu Picchu, the Andes’ most magnificent and overexposed pilgrimage destination. On the way to the big MP, however, I stopped over for a few days in a town called Ollantaytambo, about halfway up the Sacred Valley, where I wanted to visit yet another nonprofit that a friend back home had helped to found. Ollantaytambo is a village of about 2,000 at the confluence of two rivers—the Urubamba, which carves out the Sacred Valley to Machu Picchu, and the Patakancha, which descends from the mountains and flows through the town in a series of ingenious stone aqueducts. Whereas most of ancient Cusco was destroyed by the Spanish, the residents of quiet Ollantaytambo still walk the same narrow stone streets laid by their ancestors, and they’ve incorporated the old Inca walls and doorways into their small houses. On both mountainsides hemming in the village are dramatic ruins of stone temples, storehouses, and farming terraces. The largest complex is a ticketed attraction on par with Machu Picchu, but the others are open to anyone willing to do some hillside scrambling. I spent a couple of afternoons there, picking my way across the mountains from ruin to ruin, enjoying the lateral exploration of a vertical landscape. Wandering among the relics was a nice reminder that there’s more to do on a mountain besides get to the top of it.

Ollantaytambo has the region’s only high school, which enrolls students from a wide radius of mountain communities. And by and large, they are boys. Many of the villages are a full day’s walk from town, so sending kids to school means boarding them in Ollantaytambo—an expensive proposition for families, both in terms of lost labor and room and board. So you send only your brightest prospects, and in a heavily patriarchal society, that means your sons, by default. For most Quechua girls around the Sacred Valley, sixth grade tends to be the end of formal education.

The nonprofit I stopped by was called the Sacred Valley Project, a small dorm in town that offers free housing, tutoring, and support for Quechua girls pursuing secondary education. The group has just two full-time staffers—a kindly Argentinean program director and a college-aged, live-in “dorm mother”—and at the time of my visit, they were also hosting a mother-daughter pair of volunteers from Connecticut. On the day that I dropped in, the dorm’s residents were just arriving with their parents for a kick-off dinner to celebrate the new school year. They were a shy and well-behaved bunch of otherwise prototypical teens, dressed in denim and sweaters and giggling among themselves as they toured their new rooms. The fathers were brisk and polite, the mothers mostly silent. Many spoke only Quechua. They wore the traditional braids and bowler hats of Andean women, and on their backs, they carried their trademark woven blankets, brightly colored and deftly wrapped around large, mysterious bundles.

“There’s a game we sometimes play,” one of the Connecticut volunteers confided in me, indicating the bundles. “We call it ‘Baby or Vegetables?’ ”

I spent part of the day helping the women shuck corn and wash dishes. Later, I tried some chicha with the men, the tangy fermented corn drink that Thompson called “the Andes’ answ

er to home brew.” After a dinner of chicken and corn, I listened while the parents delivered short speeches, impressing upon their daughters the importance of good behavior and the value of this opportunity. The girls go home on weekends (an eight-hour walk, in some cases), and the parents meet at the dorm periodically throughout the year to gauge the girls’ progress and discuss any concerns. That evening, everybody signed a participation covenant with a number of conditions. The one that jumped out at me was the no-pregnancy clause, a stark reminder of what a fourteen-year-old Quechua girl’s life might be like in the absence of education.

I tried chatting up the girls a little, but they were mostly shy and probably appalled at my Spanish. Dina, one of the more outgoing students, was from a village called Pallata, about five miles up the Rio Patakancha, and she walked to and from her home every Friday and Sunday. Her favorite subject was math, she said, and she hoped she could be a teacher someday. I asked whether she had read any of the books on the sparsely filled bookshelf in the study room. She smiled bashfully and said, “I tried that one,” pointing to a Spanish copy of In Cold Blood. The girls were timid, but they seemed bright and driven. Thompson had gone up into hill towns just like Pallata to take photos of ragged-looking Quechua farmers behind their ox-drawn plows. I wondered what he would make of their great-granddaughters trying to plow through Truman Capote.

“Are you going to Machu Picchu?” Dina asked me. The girls had a trip planned later in the year, and they seemed excited. None of them had ever been. Some of them had never been to Cusco, just two hours away by bus.

“You can walk there, you know,” said another of the girls, timidly. She had maybe overheard me telling the program director that I wasn’t looking forward to riding the expensive and crowded tourist train. Her family was from a village not far from where the road ended, and of course, the girls and their families walked just about everywhere. I asked the program director about it, and she said that, yes, the local people regularly walked alongside the train tracks to get to the farms and pueblitos along the muddy Rio Urubamba. It was a seventeen-mile walk to reach Machu Picchu from the end of the auto road—a full day’s hike with my backpack. Along the way were a few short railroad tunnels, and technically it was illegal, but I was taken with the idea. Looking around the dorms of the Sacred Valley Project that afternoon, seeing the sandaled moms who had walked eight hours to send their kids off to high school, it was hard to imagine sitting in a cushy Pullman, staring out the windows at the very same women making the journey on foot. In a weird way, a long day’s slog through the Quechua’s ancestral homeland suddenly seemed like the least I could do.

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America