- Home

- Brian Kevin

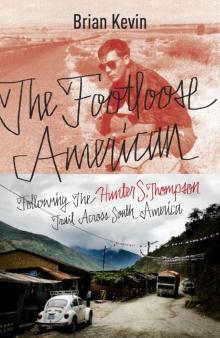

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America Page 15

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America Read online

Page 15

At one point, I turned a corner to find the rear of an inflatable castle shaking gelatinously. Elsewhere, I almost strolled right onto a dusty BMX track. The boys lined up there straddled every manner of bicycle, from fat-bottom cruisers to high-end mountain bikes two sizes too big. The bleachers next to the tennis courts were only half-full, but the crowd cheered wildly after every point, and I thought of the courts back at the Cali country club, with their televised tournament and polite applause. Next to the bleachers were two long concrete pitches of an indeterminate purpose—too long for horseshoes, too short to land a plane on.

“Cariocaaas!”

Kites, model airplanes, a handful of whirring remote-controlled machines—even the air was lively at Parque La Carolina. All throughout the park snaked a concrete channel filled with crazily listing paddleboats, their occupants screaming and spraying carioca from boat to boat. A little boy peed off a dock while his mom sat next to him, breastfeeding. Onshore, a single paddleboat leaned upside-down against a eucalyptus tree, looking like the fallout from some perplexing accident. Beneath it, a golden retriever in shorts and a blue tank top was snoozing peacefully.

The pièce de résistance was a full-sized jetliner, painted nose-to-tail with a graffiti mural and parked permanently over a patch of scuffed concrete. The plane was teeming with kids and teenagers, climbing onto the wings via a metal staircase, clinging to the rudder, dangling out the windows, strolling nonchalantly across the fuselage. Everyone was entering via a small tear in a surrounding chain-link fence, but from the stairs and the twisty slide coming out of the cockpit, the airplane seemed to be an official playground component. For several minutes I just stood at the fence, wishing like hell to be a ten-year-old again. Laughter ricocheted off the pavement, and a contingent of moms looked up from the ground, watching like helpless stewardesses during some bizarre passenger rebellion.

Some other day, I might have thought about how a jaw-dropping park like this is a testament to the kind of lavish civic spending that apparently marks Ecuador as a fearsome socialist dystopia. But I wasn’t thinking about that. I was lost in a reverie of dopey, wholesome camaraderie, too busy kicking soccer balls and licking ice-cream cones to put the scene in any kind of geopolitical context. This is something that travel does, I thought: It allows fun to smooth over all the difficult questions about how to live and be governed and who’s oppressing whom. There are no social theorists standing around a bouncy castle. So maybe all those libertines back at the Secret Garden were on to something.

It occurred to me that Thompson didn’t really do a lot of this, this kind of wandering around through the pleasantly pedestrian tableau that’s behind the curtain in all but your most chaotic cities—judging from his letters and articles, anyway, which tend to dwell on the cocktail chatter of expats, the machinations of the political class, and the often turbulent goings-on outside the windows of his downtown hotels. Thompson might have pre-dated the Gringo Trail, but even without a laptop or a hosteling card, he seems to have had a hard time breaking out of his own cultural orbit. Part of this was an occupational hazard, I suppose. You can’t cover the Cold War from a jungle gym in Parque La Carolina. Or maybe it was a conscious choice. Maybe Thompson knew that you can only watch so many laughing toddlers stumble by—conductor overalls covered in carioca, grinning parents in hot pursuit—before it affects your ability to take international relations seriously.

That night, I did go out with the hostel crowd, down to a cobblestone pedestrian strip in the Old Town, where hundreds of people were hopping from bar to bar, spraying thousands of bottles of carioca. Music floated out the open café windows, and the street was a melee of locals and tourists alike, gringos and quiteños making zero distinction as they gleefully smothered one another in soft white foam.

IV

Forget Gringolandia and the Secret Garden—when it comes to gringo enclaves abroad, there’s really no substitute for the US embassy. My cab pulled up outside the embassy’s nine-foot walls just two days after Carnaval. From the outside, the complex looks like the world headquarters of some colossal association of narcoleptic insurance salesmen. It is massive, boxy, and extremely drab. If not for a small seal with a bored-looking eagle on it, you might walk right past the place and not recognize it. Except that you’re not likely to be walking at all, because the campus is in a rather distant neighborhood on the north edge of town. It was inaugurated in 2008, the newest embassy building on the continent, and both the walls and the remote location are legacies of a State Department construction policy that, until recently, emphasized security over aesthetics, local accessibility, and, apparently, good taste.

Inside the walls, the buildings are a tiny bit sleeker—maybe less like a boring insurance company and more like a boring software company. Following a security shakedown that made the TSA line at La Guardia look like a nice visit to Grandma’s, I found myself in a Spartan marble-and-brick reception area, admiring some landscape paintings and listening to two Spanish-speaking guards discuss how they liked their sushi. I set my water bottle on an American-flag coaster and thought how nice it was to be back on American soil. Only later did I learn that the externality of US embassies is actually a myth, and that I was, in fact, still quite solidly on Ecuadorian soil, albeit with some special rules.

I was met by Counselor for Public Affairs Wes Carrington, Public Diplomacy Officer Jennifer Lawson, and Cultural Affairs Officer Lisa Swenarski, three of the four heads of the Public Affairs Section of the US diplomatic mission in Quito. The USIS that Thompson profiled in 1962 had been formed by Dwight Eisenhower nine years earlier, a direct response to the Cold War. In 1999, it was broken up and its functions divided. A new, DC-based agency was put in charge of overseas broadcasting, while the State Department’s Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs bureaus took over the promotion of American views and interests on the ground. All but the smallest American embassies have a Public Affairs Section today. Not surprisingly, the largest PAS is at the embassy in Kabul, with an American staff of twenty. That Carrington’s staff in Quito is only a few positions smaller gives some idea of the challenge of public diplomacy in “anti-imperialist” Ecuador.

“How was Carnaval?” Carrington asked, shaking my hand. He was a clean-shaven guy on the cusp of his fifties, with a silver paisley tie that matched his salt-and-pepper hair. He spoke with the easygoing authority of somebody who talks to strangers for a living.

“I think I’m still cleaning the carioca out of my ears,” I said. “It’s quite a campus you’ve got here.”

It was nice, they all agreed, not that any of them had been there all that long. Foreign Service officers rotate into new posts every two or three years, a strategy designed to prevent what diplomats refer to as “clientitis,” or an increasing allegiance to one’s host country rather than the United States. Of the three, Carrington was the elder statesman, coming up on the end of his term in Ecuador. He’d been with the State Department since 1989 and served abroad since 2002, with rotations in Brazil and Portugal. Lawson and Swenarski were newer to both Ecuador and the Foreign Service, but between them, they’d had postings in politically “hot” countries like Serbia, India, and Saudi Arabia.

The four of us headed to the cafeteria, where a few tables of power-suited staffers were watching CNN and quietly munching chicken and rice (Ecuadorian food, I noticed—not burgers and fries). I’d already forwarded Carrington a copy of “How Democracy Is Nudged,” and as soon as we’d sat down with our trays, he apologized that the embassy lacked the romantic chaos of Thompson’s USIS office.

“I’m afraid things are rarely that exciting around here,” he said, lifting a forkful of rice.

“Well, except maybe when they PNGed the ambassador,” Lawson said.

“Oh yeah,” said Carrington between chews. “That was exciting, but that doesn’t happen very often.”

It really doesn’t, which is why it was a big deal when President Correa expelled US ambassador Heather Hodges in 2011, declaring

her persona non grata (or “PNGing” her, in diplomat-speak) in retaliation for a WikiLeaked cable in which she accused Correa of condoning police corruption. After announcing her expulsion, Correa declared indignantly, “Colonialism in Latin America is finished.” Only six US ambassadors have been PNGed from their host countries in the last forty years, and three of those have been in the so-called Bolivarian states of the Andes. In Bolivia, the US ambassador was booted in 2008, accused by leftist-populist president Evo Morales of fomenting political unrest. Venezuela’s Chávez PNGed his US ambassador the very next day. It’s a symbolic gesture, but a serious one. The ambassador and his or her family have just seventy-two hours to leave the country, which accounted for a lot of the temporary excitement around the Quito embassy. Diplomatic relations continue in the ambassador’s absence, with a chargé d’affaires filling his or her shoes, but relations are often strained. When I visited Quito, the embassy was still working without an ambassador. A new one was reinstated three months later, and negotiations are still ongoing to restore full ties with Venezuela and Bolivia.

In the wake of the expulsion, Carrington’s team had a media circus on their hands, but ordinarily life around the PAS offices moves at about the same pace as your average small Manhattan PR firm—and with significantly less glamour. The international propaganda biz has changed somewhat since the fall of communism, and today’s heirs to the USIS are as much administrators and event promoters as artful spin doctors. Sure, disseminating news from a US perspective is still part of the job. Public Affairs officers issue press releases to the Ecuadorian media just like any other organization, and the embassy distributes an in-house newsradio show, Reportajes, to some 120 stations across the country. I listened to a couple of episodes and found the stories “not so much slanted as selected,” as Thompson described similar USIS efforts in 1962. There was a piece about Hugo Chávez returning to Cuba for further cancer treatment, a story that Venezuelan officials regularly played down. There was coverage of Drug War negotiations at the then-ongoing Summit of the Americas in Cartagena, Colombia—an event that only garnered coverage in the United States thanks to a titillating Secret Service prostitution scandal. Meanwhile, quite apart from the embassies, the DC-based, semi-independent Voice of America networks broadcast radio and TV programs in forty-three languages on a worldwide network of transmitting stations.

But to hear my hosts tell it around the lunch table, managing the news is less important to the mission of public diplomacy than it once was.

“We’ve had a big shift of emphasis over the years to language and exchange programs,” explained Swenarski, the cultural affairs officer. These days, she said, a lot of the bureau’s money and manpower goes into supporting public and private English-language learning centers, sending students and professionals to study in the United States, and hosting American speakers and performers in Ecuador. The USIS in Thompson’s story brought a commie radio station to its knees. The PAS in Quito recently brought an alt-country band to the Amazon.

Without any Cold War antagonists to outfox, today’s battle for hearts and minds seems less like an ideological contest and more like a slightly crunchy outreach campaign. The bulk of the PAS’s efforts are actually built around the rather simple and charming notion that the more foreigners know about the United States, the more they will like us. So the agency sponsors a vast network of cultural centers and “American corners”—libraries and community spaces with English-language books and movies, occasional free lectures, and cultural displays. Come for the free Internet, stay for the exhibit on civil rights! Lawson mentioned working with administrators and student groups at local universities, trying to drum up support for American studies curricula. Swenarski described a few of the PAS’s cultural programs, an impressive slate of tours, exhibits, and performances that pivot around annual themes. Last year’s “Rural America” theme, for example, brought in bluegrass musicians and school presentations about the rodeo. The year before had a black culture motif, with New Orleans brass brands and step-dancing troupes. Programs like these, it seemed to me, still followed rather literally what had been the old tagline of the USIS: “Telling America’s story to the world.”

International exchanges, meanwhile, are arguably at the heart of the PAS’s mission. Youth ambassador and leadership programs send Ecuadorian students to workshops and conferences in the United States. Similar programs for adults target leaders in business, government, education, and media. To fully grasp the potential payoff of these field trips, consider that four justices on the Ecuadorian equivalent of the Supreme Court are alums of such programs, as are some three hundred heads of state or cabinet-level ministers worldwide. It’s a forward-looking strategy, one that banks on the notion that today’s familiarity with American culture will translate into tomorrow’s support for American policies.

“The generation that knows you and loves you won’t always be around,” Swenarski said. “I’d say fifteen to twenty-five is the target age that we’re trying to reach.”

Of course, even the kinder, gentler face of soft power still has its turf wars. Around the world, for instance, Confucius Institutes sponsored by the Chinese government are increasingly muscling in on cultural territory dominated by PAS-backed language programs and community centers. The first one in Ecuador opened at Quito’s Universidad San Francisco in 2010, and seeing as how China has invested more than $8 billion in the country since 2009, a quiteño could be forgiven for wanting to pick up some Mandarin. That undermines the PAS mission, Swenarski explains, since every hour that an Ecuadorian spends learning tea ceremonies at a Confucius Institute is an hour she’s not learning the similarly delightful traditions of the supposed Yankee imperialists.

Unlike the USIS and its America-bashing broadcaster, the PAS is not likely to torpedo the Universidad San Francisco for hosting a Chinese public diplomacy arm. Very much like their predecessors, however, today’s democracy-nudgers still pay close attention to how the United States is represented in local media. After lunch, the two junior diplomats excused themselves, and Carrington led me upstairs to a nondescript door at the edge of a cubicle complex.

“This is the monitoring room,” he said, “probably the only place in the building that has a little bit of a secret-agent vibe.”

Inside was a fluorescent-lit room with cheap office furniture, utility shelves, and a half dozen PCs. Nothing particularly glamorous about it. It reminded me of the ammonia-stink janitor’s closet that my high school handed over to the AV club, except that my AV club never had a seventy-two-inch monitor on the wall with inlaid screens simultaneously airing every Ecuadorian TV network.

“Usually we’ve got a couple of guys in here,” Carrington said, “monitoring for any mentions of the US or US policy. I guess they’re at lunch.”

I stared at the grid of talking heads and telenovelas. It was a bit hypnotic, like the flickering, towering displays at an appliance store. “I know a couple of news junkies who could really get into this,” I said.

“Yeah, mostly we get former radio and TV guys. Of course, we watch the newspapers and the Web too. Did you know three different papers reprinted that New York Times editorial about Correa this morning?”

The week before, Ecuador’s National Court of Justice had upheld a conviction in a libel suit brought by Correa against the directors and a former editor of El Universo, the country’s largest paper. The journalists were fined $42 million and sentenced to three-year prison terms for publishing an editorial that called Correa a “dictator” and alleged he had put civilians in danger by ordering troops to open fire during a 2010 police rebellion. “Ha brillado la verdad,” Correa had announced from the steps of the courthouse. The truth has shone through. It was his biggest lawsuit against journalists, although not his first. The trial was full of abnormalities, and the New York Times echoed other media outlets and watchdog groups when it called the ruling “a staggering, shameful blow to the country’s democracy.” Under heavy pressure, Correa issued a pardo

n a couple of weeks later.

“So, what do you do with everything you find?” I asked Carrington.

“Sort it by topic and organize it into a daily dossier, available for other diplomats and policymakers. I can get you a copy.” He motioned for me to follow him to his office.

We walked through a dense jungle of cubicles, quiet but for the hum of monitors, the clacking of keyboards, and the occasional muffled whiff of phone conversation. Framed pictures of national parks and other American landmarks hung on the walls at regular intervals. The whole place had a very corporate vibe. If this was telling America’s story, I thought, then storytelling had become rather systematized.

Carrington’s office was clean and simple—a few crowded bookshelves, pictures of his kids, a framed map of Chesapeake Bay. On a wall-mounted flat-screen, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was giving a speech in London. For a moment, I thought maybe the State Department had an all-Hillary channel, à la The Truman Show, but it was just CNN.

“It’s a particularly fat one today on account of the El Universo ruling,” Carrington said, handing me a thick folder of photocopied news articles. We took a seat as I leafed through. It was divided into sections, with headings like “Coverage of Outreach Efforts,” “Economic News and Opinion,” “Counternarcotics,” and “Freedom of the Press.” Many of the headlines trumpeted Correa’s refusal to stay the Universo sentences, as requested by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Correa had countered that the commission was dominated by “certain hegemonic states,” a not-so-subtle jab at supposed US meddling.

On the TV, Hillary was offering condolences on the deaths of two journalists, a reporter and a photographer who’d snuck into Syria, covering the uprising there in defiance of that country’s government. Carrington and I had both turned to listen when a loud buzz from the PA drowned out the television. Suddenly, a man’s recorded voice filled the room—calm, but with a no-bullshit tone of authority.

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America

The Footloose American: Following the Hunter S. Thompson Trail Across South America